Tablecloth and napkin folding is often seen as a predecessor to paperfolding. I do not intend to write much about this subject since it has already been so well covered in Joan Sallas’ superb book ‘Folded Beauty’. It might be worth saying, however, that there are really three, quite distinct, types of tablecloth and napkin folding, and that only one of them can be shown to have had direct influence on the development of paperfolding.

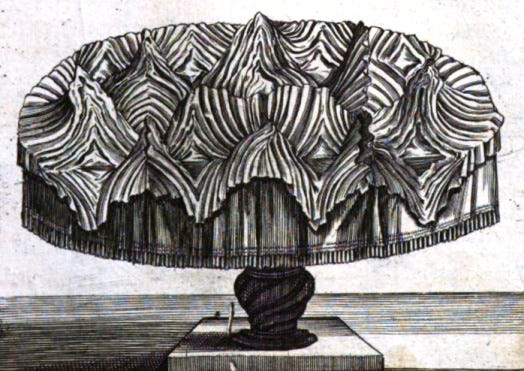

The most amazing of the three is the folding of napkins (though in many cases rather large ones) into highly ornate centrepieces, of the kind shown in the photo above. Those shown in the photo are reconstructions, folded by Joan Sallas, of masterpieces from the book 'Neues Trenchier-und Plicatur-Büchlein' by Andreas Klett, which was first published in 1657. They clearly demonstrate the heights which napkin folding had reached at that date.

I would guess that there were very few practitioners (unless they were perfect Dutch kitchen-maids) who could achieve this level of complexity, and, perhaps for that reason, or perhaps because it simply went out of fashion, this type of complex decorative napkin folding was only around for some 80 or so years. The earliest treatise on the subject was 'Trattato delle piegature', by Mattia Giegher, which was published in 1629 and the last was 'Vollständige Haus-und Land-Bibliothec' by Andreas Glorez, which was published in 1699.

There are a few minor mentions of complex decorative napkin folding thereafter, but nothing that amounts to a substantial explanation of how it could be done.

The only substantive connection between this type of napkin folding and paperfolding is a passage in 'Aanhangzel volmaakte Hollandsche keuken-meid' (the perfect Dutch kitchen-maid) by Jan Willem Claus van Laar, which , was published in Amsterdam in 1746, which says, 'if one, with a little care, tries it oneself with a piece of paper', which suggests that paper was sometimes used to practice napkin folding techniques.

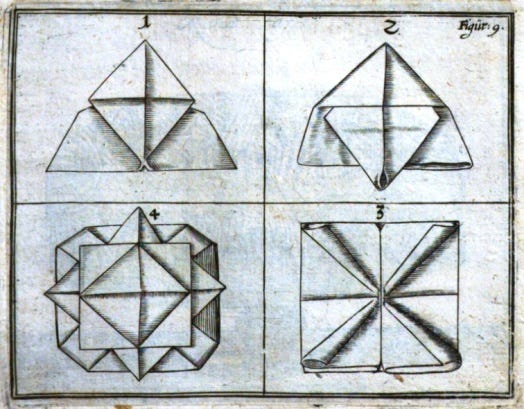

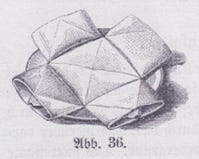

The second type, the folding of complete tablecloths, seems to have been limited to the decoration of side tables. Here is an illustration of such a folded tablecloth from an earlier book, ‘Vollständiges und von neuem vermehrtes Trincir-Buch' by Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, which was published in 1652.

The third type of napkin folding was the folding of those small individual napkins that were set on the table for guests to use. Several basic designs for these types of folds can be found in Harsdörffer’s 1652 book mentioned above, and it is, of course, this kind of napkin folding that has survived until the present day.

We can clearly link this third type of napkin folding to the development of paperfolding. 'L'Escole parfaite des officiers de bouche; contenant le vray maistre-d'hotel, le grand escuyer tranchant, le sommelier royal, le confiturier royal, le cuisinier royal et le patissier royal' which was published in Paris in 1662 (they did like their book titles long in those days), contains instructions for folding a ‘Croix de Sainct Esprit' and a 'Croix de Lorraine'.

The first of these is what we might now call the triple blintz basic form (otherwise known as Froebel’s third groundform), and the second, which is developed from it, has become a well known Froebelian Fold of Life, which is nowadays usually known just as ‘The Cross’.

All this is rather by way of prologue. I expect that your Facebook feed, if you have one, is, like mine nowadays, mostly full of junk, and only occasionally allows you that insight into your friends lives that is the reason we once thought it worth subscribing.

One of the pieces of junk that appeared in my feed over Easter was an article about a neatly folded napkin said to have been found in Jesus’ empty tomb after his resurrection. Naturally this caught my eye.

The essence of the post was this: ‘The Gospel of John (John 20:7) tells us that the napkin, which was placed over the face of Jesus, was not just thrown aside like the grave clothes … (but) …. was neatly folded … ’ The idea that John’s Gospel might mention a neatly folded napkin intrigued me.

Now, few people outside my immediate family know that when I left school I went to theological college and completed two years of study towards a London University degree in Divinity. Ill health during the second year (and perhaps some lack of dedication to my studies) meant that I didn’t return to complete my third and final year. Nevertheless, I enjoyed two years of philosophy, comparative religion and the history of Christian beliefs and doctrine, and suffered through two years of the study of Old Testament Hebrew and New Testament Greek. I can remember much of the former but nothing whatsoever of the latter.

Using my expert knowledge (ie Googling it), I discovered that the earliest version of John 20 v 7 which mentions a ‘napkin’ can be found in the partial translation of the Bible into English published by William Tyndale in 1526. This reads, ‘and the napkyn that was aboute his heed not lyinge with the lynnen clothe but wrapped togeder in a place by it selfe.’ (The image below is the opening page of John’s gospel from the same version.)

This wording was retained, in a modernised form, in the much more familiar King James version of 1611, ‘And the napkin, that was about his head, not lying with the linen clothes, but wrapped together in a place by itself.’ (The King James version, supposedly the work of a committee of scholars and church worthies, is, by some estimates, as much as 70% William Tyndale’s work.)

Encouraged by the 1526 date, despite the lack of any reference to folding, (was this the earliest reference to any kind of napkin in English?) I decided to look up the original Greek text (or at least the best reconstruction of the original Greek text that scholars have been able to put together, which is not necessarily the same thing). I discovered that the word translated as ‘napkyn’ by William Tyndale is ‘soudarion’ (σουδάριον), which doesn’t mean a napkin as we now understand it, but something much more akin to a handkerchief, a cloth used to wipe off sweat and possibly to blow one’s nose in, or in this context, such a cloth used to cover the face of a corpse. The word translated ‘wrapped togeder’ is ‘entetyligmenon’ (ἐντετυλιγμένον), a comparatively rare word that can probably bear the meaning ‘folded’ but also ‘rolled’, or simply ‘crumpled up’. ‘Wrapped togeder’ seems to be a way to express the uncertainty of how the word should be rendered in English.

It would have been wonderful if William Tyndale really had mentioned a ‘neatly folded napkin’ in 1526, but, unfortunately, he didn’t. An Easter wild goose chase.

One codicil. While looking to see if there were earlier mentions of napkins in the English language, I came across several mentions of the date 1384/5, but none of them gave a source for the reference. Just out of interest, I looked this up as well and found that it originates from the Oxford English Dictionary, which states that the information comes from ‘J. T. Fowler, Extracts Account Rolls of Abbey of Durham (1898) vol. I. 265 (Middle English Dictionary)’. I have not attempted to locate that document. Curiosity has its limits.

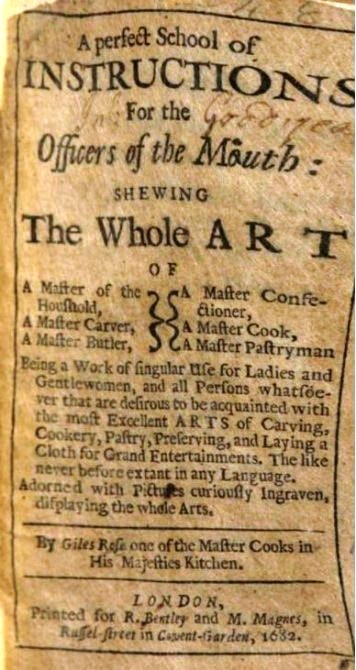

So, if 1384/5 is the earliest reference in English to a napkin of any kind, what is the earliest reference to a folded napkin? Well, the OED is no help on this, and it remains an open question. Maybe you could tell me? The earliest I know of is found in 'A Perfect School of Instructions for the Officers of the Mouth: Shewing the whole art of A Master of the Houshold, A Master Carver, A Master Butler, A Master Confectioner, A Master Cook, A Master Pastryman' by Giles Rose, published in London in 1682, which is a translation into English of 'L'Escole parfaite des officiers de bouche etc’ which we have already met.

Despite this book being a translation, the title page (see above) claims 'The like never before extant in any Language'. Hmmmm.

PS: There are several mentions of napkins in Shakespeare’s plays. Kudos to anyone who can name one without needing to look it up. None of these napkins, though, are ‘neatly folded’, or even folded at all.