If your German is somewhat better than mine you will know that the title of this book translates as ‘Out of paper: folded, creased, glued’. (‘Out of paper’ here meaning ‘made out of paper’, rather than being an error message from your printer.)

I first learned about this work in Gershon Legman’s famous ‘Bibliography of Paperfolding’, which he published in 1952, and although the information he gives is very minimal, it intrigued me because he says it was published in Berlin in 1940, at which time, of course, Germany was at war. I was surprised that the publication of children’s literature would continue as normal during this time. However, it seems it did, and, as it turns out, this is not the only example of a paperfolding publication from wartime Germany.

Then a few weeks ago, I came across a copy advertised on a German book sales site and couldn’t resist paying far too much to acquire it. As is the way with such things, when it arrived there was very little inside it to justify the outlay. Only two of the pages refer specifically to paperfolding per se, the rest being largely concerned with folding and gluing together paper templates to construct models of everything from fairground stalls to a windmill. The clue was in the title, of course.

I was not as disappointed as I might have been, because Edwin Corrie had meanwhile discovered that, after Germany had been defeated and partitioned in 1945, this apparently innocuous little book was banned by the Western Allies.

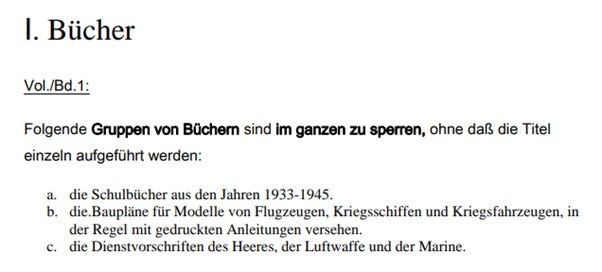

It was not alone. The online document Alliierte Zensur im Nachkriegsdeutschland gives a list of hundreds of other books that were banned at the same time. But why ban a book on papercrafts? Well, the answer is that many of the models in the book are of military vehicles and aircraft, some of which, as you might expect, are clearly marked with German military insignia.

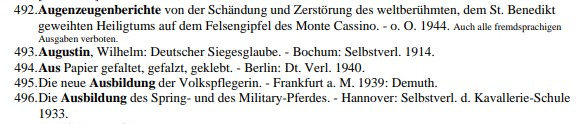

There are no Nazi symbols in the book, but it appears that it nevertheless fell foul of a blanket provision banning books containing 'construction plans for models of aircraft, warships and military vehicles'. (For correction to this paragraph see PPS below.)

Despite clearly falling within this blanket ban, the work is also banned quite specifically by name.

This, I feel, lends the book a certain cachet it might otherwise not possess.

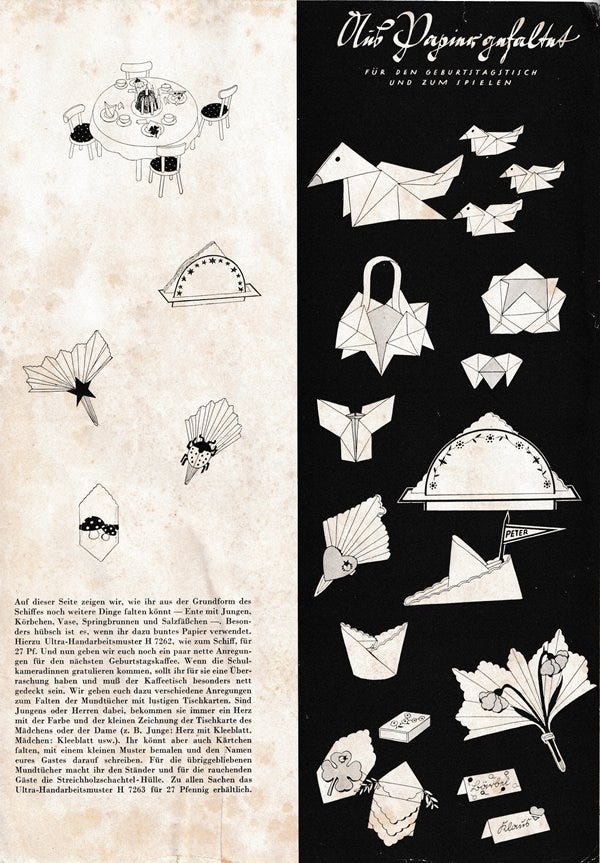

Here are the two pages which relate to paperfolding per se:

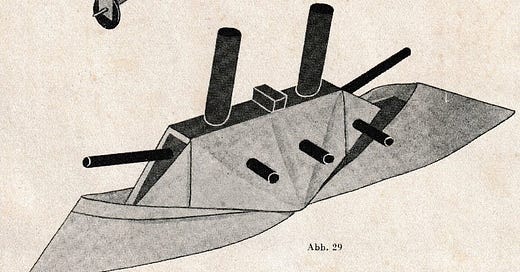

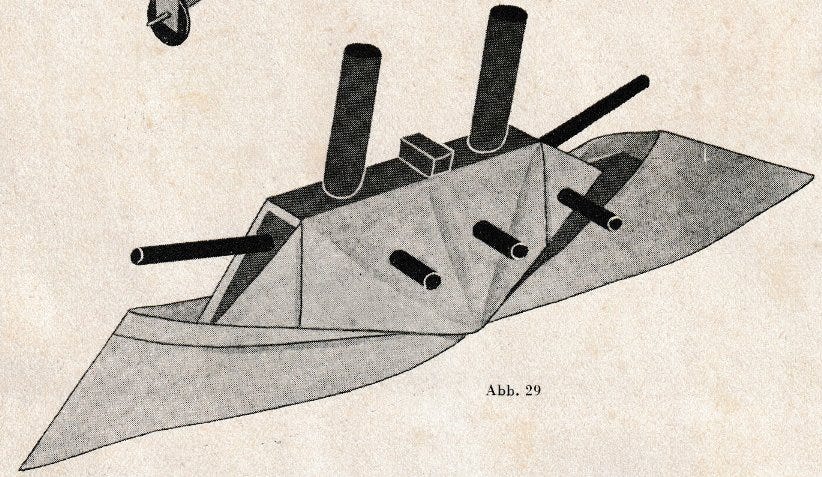

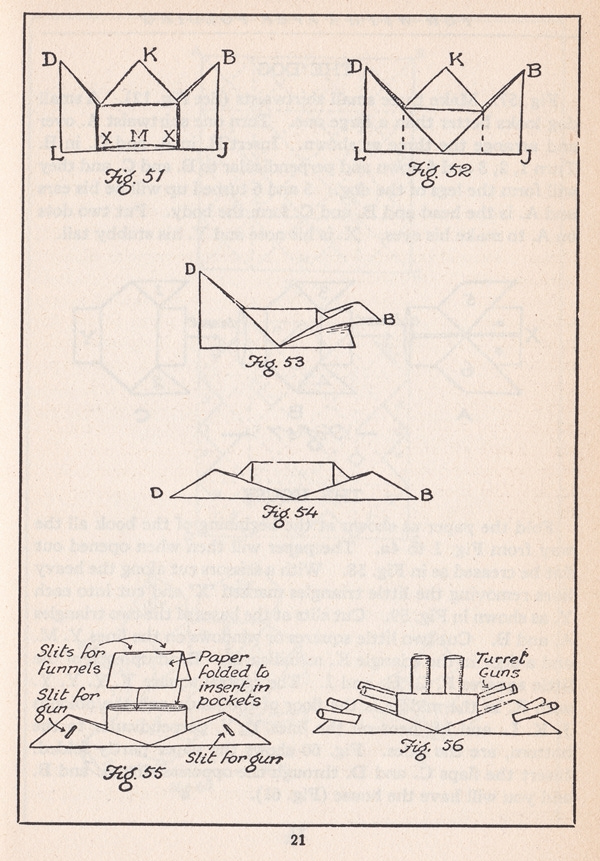

To me, the most interesting thing here is the appearance, at the foot of the first page, of a design I call ‘The Battleship’. It is very much a hybrid design. The basis is a Froebelian fold of life known as ‘The King’s Crown’, which is varied by folding each end outwards before adding funnels and guns made from rolled-up paper.

I cannot be sure that the guns and funnel in the design in ‘Aus papier: gefaltet, gefalzt, geklebt’ are made in the same way, because, although the design is pictured, there are no instructions for making it. These are contained in a separate publication ‘ultra-handcrafted pattern H7263' which the reader could obtain for an extra outlay of 27Pfennig (on top of the 90 already paid). Sharp practice, I feel! Needless to say, I do not have a copy of this second publication.

The only other book that I know contains the ‘Battleship’ design is Murray and Rigney’s ‘Fun with Paper Folding’ published in 1928. This book was published in New York, so the design was clearly intended to be made by warlike American children. But what’s sauce for the American goose is, I suppose, also sauce for the German gander.

PS I have not managed to find the document ‘Alliierte Zensur im Nachkriegsdeutschland’ elsewhere, or verify that it is genuine. However, it seems unlikely to me that anyone would go to the trouble to forge such a complex document for no particular purpose.

PPS Media Luna has pointed out (see comments) that the statement that ‘there are no Nazi symbols in the book’ is incorrect, since there is a swastika on the tail of the fighter plane, which I had somehow completely missed seeing. However, unless the Allied censor was particularly eagle-eyed (unlike me) I still think that the book was probably banned because it infringed the no 'construction plans for models of aircraft, warships and military vehicles' rule.

Origami Shuko may have been another book that suffered the same fate. When we analyzed it with Joan Sallas a few years ago, and he saw that the first pages featured two children holding the imperial flag, his reaction wasn’t surprise but relief, as he understood why the book had disappeared from circulation. Although it had been published in 1944 (Honda sometimes stated 1941), no copies remained, and it was presumed that they had vanished in the Tokyo bombing. However, years later, Akira Yoshizawa sent Gershon Legman a photocopy of the entire book. This is the copy now housed in the Museo del Origami in Colonia, the same one we reviewed with Joan Sallas. In an email exchange, Joan summarized his view: "A book that starts with the imperial flag of fascist Japan could not have been sold after 1945. Honda might have destroyed them. Or perhaps American authorities forced the publisher to destroy them. Something similar happened with German origami books after losing the war. Yoshizawa swallowed the bitterness, but the resentment lingered. Over the years, he saw the success Honda was achieving while he couldn’t publish a single book abroad." There it was: the key to the mystery of the book's disappearance and the anger Yoshizawa felt as he watched his first significant collaboration vanish.

The ‘Battleship’ design in Murray and Rigney’s "Fun with Paper Folding" published in 1928, and in "Aus papier: gefaltet, gefalzt, gekleb" in 1940 has been also published in:

- The Danish book "Folderier" only in the 3rd (and last) edition in 1947 as we can see via

https://papirfoldning.dk/historie/folderier_en.html

- The German book by Walter Sperling "Papier-Spiele" in 1955 and his English translation "How to Make Things Out of Paper" in 1961. In both case you can his drawing on the front cover.