In his famous book 'The Natural History of Selbourne', published in 1789, Gilbert White mentioned keeping a cricket in a paper cage ‘set in the sun and supplied with plants moistened with water’. In these circumstances the cricket ‘will feed and thrive, and become so merry and loud as to be irksome’. However, ‘if the plants are not wetted it will die.’

Keeping crickets, grasshoppers and other noise-making insects, in paper cages seems to have been something of a thing in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. References to keeping insects in cages do not always specify that the cages were made from paper, however, it seems to me that this is likely to have usually been the case , since the advantage of a paper cage over, for instance, a wire one, would be that it would act to amplify any sound the insect made, which was, I think, rather the point.

The earliest reference we have to this practice is part of a line in John Webster’s play ‘The Tragedy of the Dutchesse of Malfy’, published in 1623, which talks about ‘those Paper prisons boys use to keepe flies in’.

This practice was not unique to England. In 1670, the Spanish writer D Diego de Saabedra mentioned 'jaulas de grillos' (cricket cages) in his 'Republica Literaria':

An English translation, 'The Commonwealth of Learning', published in 1705, rendered this as:

The practice was also found in Germany. In 1761, for instance, 'The London Chronicle' ran an article which included a description of a boy selling grasshoppers to the inhabitants of Hamburg in 'little paper cages like doll's houses'.

Similarly, in his novella, 'Le Colonel Chabert', published in Paris in 1832, Honore Balzac wrote of 'hannetons enfermes par les ecoliers dans les cornets de papier' which translates as 'cockchafers locked up by schoolchildren in paper cones'.

And 'The Handbook of Engraved Gems' by C W King, which was published in London in 1866, contains mention of crickets kept in paper cages by children in Italy.

So the practice of keeping insects in paper cages was widespread in Europe (and indeed beyond, though I have not presented the evidence for this), but what were these paper cages like? And how were they made?

Eric Kenneway believed that the line ‘Paper prisons boys use to keepe flies in’ in John Webster’s play ‘surely refers to the WATERBOMB’ (‘ABC of Origami’, British Origami Society Booklet 47, published in 1994) and even David Lister seems to have subscribed to this belief, writing ‘This surely can be a reference to none other than the waterbomb’ in his article about Old European Origami (although he was more circumspect in another article written about Really Old Origami saying only ‘This seems likely to refer to the familiar waterbomb’ and ‘the paper prisons may have been something quite different’).

Doubt about this identification arises because, while there is plenty of evidence to show that waterbombs were used as prisons for flies in the late 19th Century, there is none, so far, to show that this happened at an earlier date. In fact the existence of the waterbomb design is not evidenced at all until as late as 1863.

Another clear candidate is the Catherine of Cleves Box. This is the box shown in the picture at the top of this blog, which is taken from the book 'Jeux et Jouet du Jeune Age' by Gaston Tissandier, published in Paris in 1884. This box is certainly of sufficient age, being first evidenced from as long ago as 1440, but I cannot imagine children making these in any quantity.

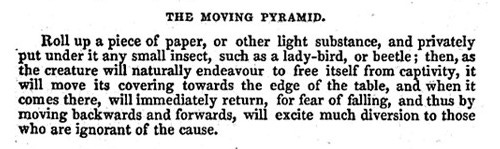

A good candidate for something more basic, and easier to mass produce, is the paper cone. We have already seen that Balzac described 'cockchafers locked up … in paper cones' (presumably paper cones whose open end had been folded, or crumpled, inwards to seal the insects inside). There is also an interesting reference to trapping insects inside rolled-up paper pyramids (i.e. paper cones) in 'The Boy's Own Book' by William Clarke, which was was published in London in 1828.

This is probably as far as we can go. All three of these designs have been used as paper prisons of one kind or another at specific places in particular times, but there is no compelling evidence that any of them are the paper prisons referred to in the earliest sources, and so it clearly remains possible that these early paper prisons were made in some other way entirely. Hopefully, some better descriptive, or even pictorial, evidence will turn up soon. If it does, I will report it here.

If you are interested in reading more of the original sources on this subject (many of which I have not mentioned) you can find them here.