The history of paper hats, or at least of paper headgear, is a long and fascinating one, but it took a particularly intriguing detour at the very beginning of the 19th century when workmen in certain trades started wearing square-shaped paper hats at work.

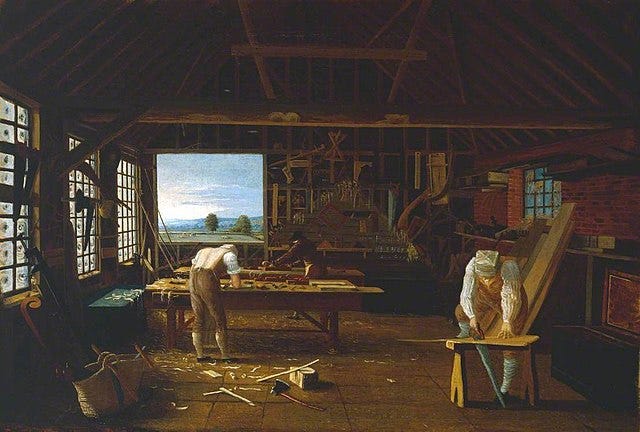

This painting by John Hill, painted around 1800, and titled ‘‘Interior of the Carpenter's Shop at Forty Hill Enfield' is the earliest evidence we have of this trend.

It is not at all clear why this tend, or fashion, began. I say ‘fashion’, because, while it is understandable that carpenters might want to wear a hat to keep warm, or to keep sawdust or shavings out of their hair, the advantage of a paper hat over, for instance, a knitted cap is not immediately obvious. At least to me.

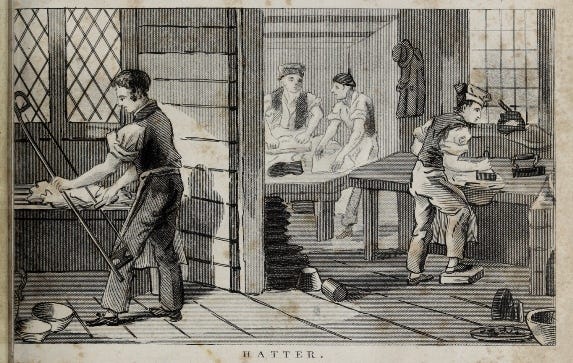

Paper-makers were also early adopters of these hats (and in a way that makes more sense because they clearly had plenty of scrap paper to hand) and many other trades followed suit. We have illustrations of glass-blowers, printers, hatters, coopers, lace-makers and many more, wearing these square-shaped paper hats at work.

Workmen’s paper hats were not, however, ubiquitous. It is much easier to find illustrations of workmen wearing other kinds of hats, or none at all, than of workmen wearing paper hats. And even when illustrations do feature such paper hats, such as the one of Hatters shown above, it is not unusual for some workmen in the picture to be wearing them and others not. This suggests that whether you wore a paper hat at work or not was not a matter of trade etiquette but of personal choice.

Despite this, it appears that, for cartoonists at least, the Workman’s Hat became a useful symbol for the working classes (just as a Top Hat was a useful symbol for the rich).

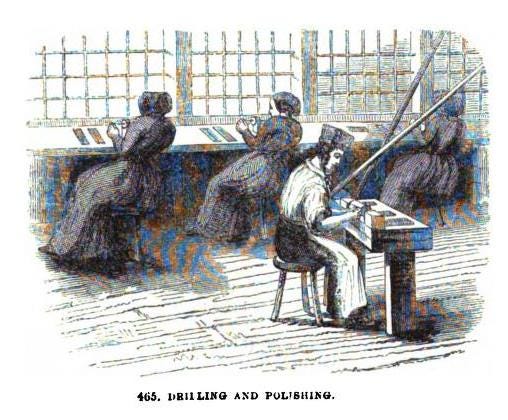

At this point I ought to note that in christening this hat ‘The Workman’s Hat’ I have fallen into a serious patriarchal error. Women also wore such hats, as evidenced by the illustration below.

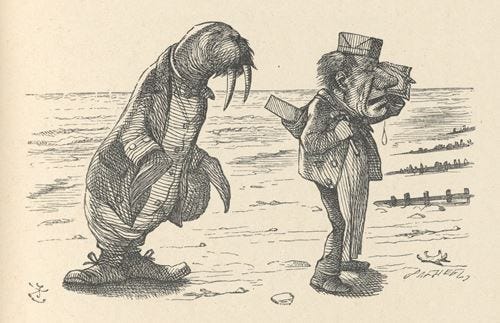

In March 2023 I was contacted by Matthew Demakos, who is interested in all things connected with Lewis Carroll, and was trying to find out how the hats shown in John Tenniel’s famous illustrations for ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ would have been made.

I was surprised to realise that I didn’t know. I had, I suppose, assumed that Workman’s Hats were somehow related to the Newspaper Hat and the Printer’s Hat, which are derived from the initial folds for the Paper Boat, but this turned out not to be the case. Matthew’s research turned up a number of descriptions of the folding (and sometimes cutting) process which showed that the Workman’s Hat was in fact developed from a waterbomb base (usually, but not always, folded in the centre of an oblong sheet). The top of the waterbomb base was then folded downwards, and the sides folded in, at back and front. Finally the brim was folded up all round to hold the folds together and the top was flattened to a square. The descriptions differed in almost every other detail, but the core of the folding process was the same in each case.

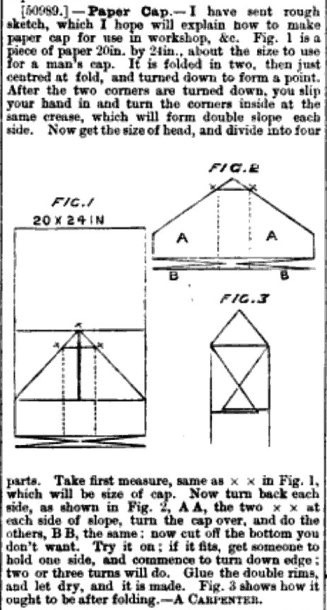

These diagrams, taken from the 'English Mechanic and World of Science' for August 24, 1883 are the best (yes, really!) of all those that Matthew found (which tells you how poor the others were. Nevertheless, by comparing them all, the basic method could be understood).

These diagrams are particularly interesting because they provide a solution to a question that had been puzzling me: How do you fold a Workman’s Hat to fit around any particular person’s size of head? One hat to fit them all? And sufficiently snugly that it doesn’t fall off? I had imagined a long process of trial, error and adjustment but the solution is much simpler than that.

You will see that in figure 2 there is a line marked xx, which is the length of the crease you make when you fold the tip of the waterbomb base downwards. That line is one quarter the length of the inside of the brim of the finished hat. Pure genius. The instructions state ‘Now get the size of the head and divide into four parts’. I have no idea how Victorian workmen did this, but one obvious way is to use a long strip of paper, curl it around the head and mark the length, then cut off any excess and fold into four. You now have a template that you can lay across the waterbomb base to find out where the downward crease should be made. The strip can be set aside for future use …

If you want to learn more about the history of the Workman’s (and Workwoman’s) Hat you can find the page where I collect information on the subject here. Matthew Demakos has also made a video on the subject, which you can find on the You Tube site of the Lewis Carroll Society of North America. This video provides other insights into the way the Workman’s Hat was made and could be varied and is well worth watching.