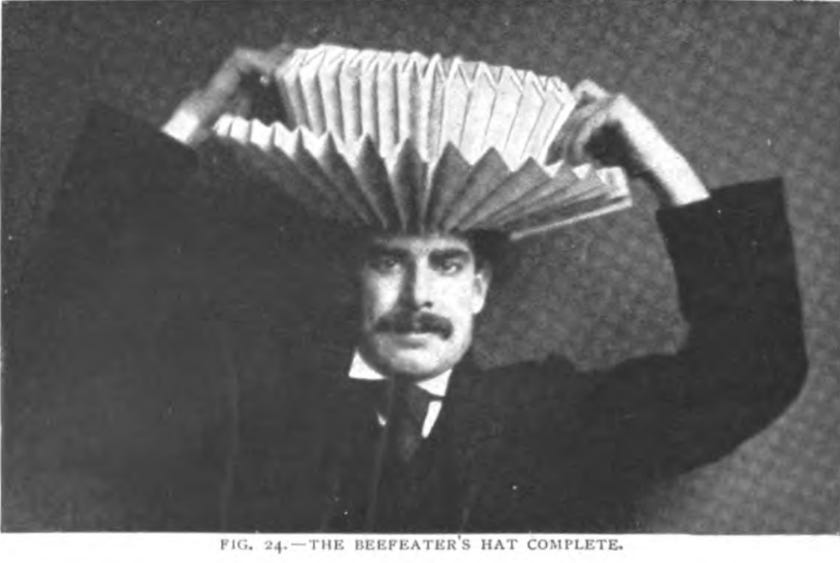

It is well known that in 1896 the famous prestidigitateur David Devant included paperfolding in the magic act which he performed at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, London. This ‘paperfolding’ was what is more commonly known as ‘Troublewit’ (though it also goes by many other names). Fortunately for us, the Strand Magazine persuaded David Devant to allow himself and his paperfolding to be featured in a photographic story, so that we know exactly what this act contained. (Not that it probably took a great deal of persuasion.)

If you don’t know Troublewit, then let the Strand magazine introduce you to what it is and how it works:

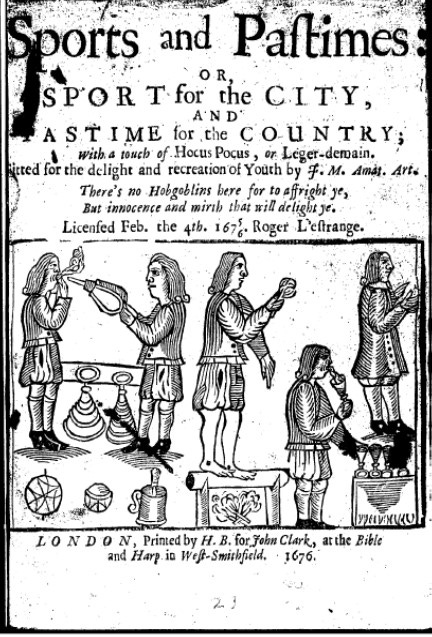

It is also well known that Troublewit was nowhere near new at this time. In fact we first learn of it two hundred and twenty years earlier in the book 'Sports and Pastimes: or, Sport for the City, and Pastime for the Country; With a touch of Hocus Pocus, or Leger-demain: Fitted for the delight and recreation of Youth' which was published in 1676, We are not certain of the name of the author, who is only identified as J M.

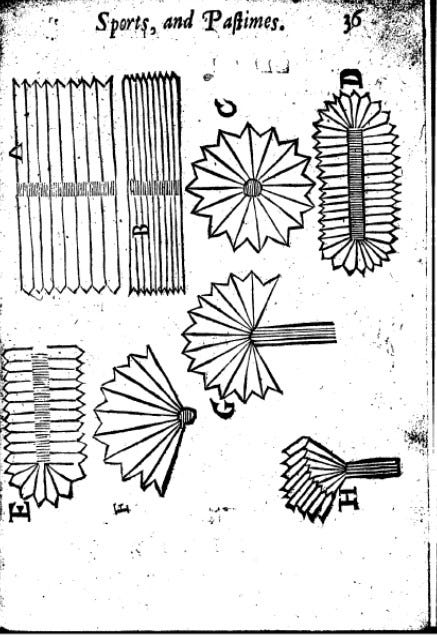

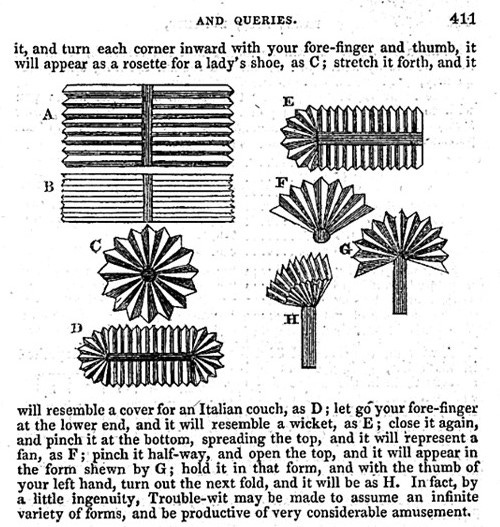

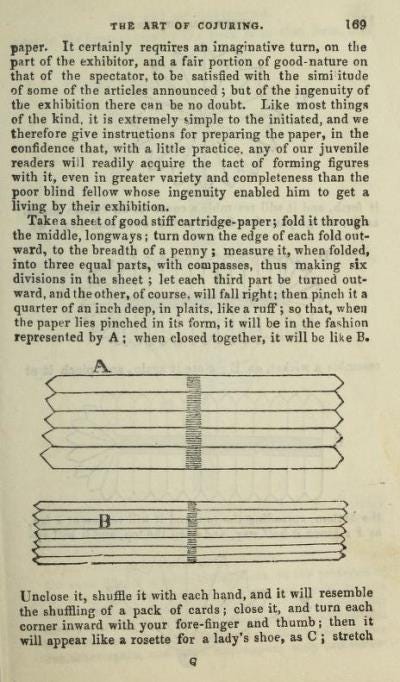

The form of Troublewit explained in this book is quite a simple one. Nevertheless it can still be manipulated into quite a number of fanciful shapes (or, at least, shapes with fanciful names). In the illustration below there are, for instance, C: ‘a Rose for a Ladies shoo’, D: ‘a cover for an Italian Coach’, E: ‘a Portal to a Noble Man’s Dore’. The author seems to say that a more complex form is possible, from which you can make such fanciful figures as ‘a Mince Pye without any Meat in it’ and ‘a Carriadge for a piece of Ordinance’. (If you want to read the whole of the description the author gives you can find it here.)

Because it uses similar folding techniques, Troublewit is sometimes thought to have developed out of complex napkin folding, but there is no evidence to support this theory, and it seems unlikely to me. Part of the reason for my scepticism is the social gulf between the two. Complex napkin folding was carried out to decorate the tables of royalty and aristocracy. Troublewit was a lowly street entertainment, performed by people who lived at the wrong end of town.

In 1881, for instance, 'Cassell's Book of Indoor Amusements, Card Games and Fireside Fun' stated that Troublewit ‘is often exhibited for profit in the public streets of populous places by members of that class of persons who prefer living by their wits to working hard.’

Somewhat earlier than this, in 1826, William Hone, writing in 'The Everyday Book and Table Book', described seeing one such member of this class of persons, who happened to be blind, which probably did not help his chances of gaining a more socially-acceptable form of gainful employment, demonstrate Troublewit in Greenwich Park.

Greenwich Park, incidentally, is one of London’s Royal Parks (i.e. a place where the Kings and Queens of England used to go hawking and hunting), and is probably most famous for being the site of the Royal Observatory (built, oddly enough, in 1675). The Royal Observatory was used to establish the location of the Greenwich Prime Meridian, now superseded by the International Reference Meridian. This imaginary baseline still runs through Greenwich Park, though no longer through the Royal Observatory.

You might think that being mentioned in one book would be sufficient fame for a blind busker, but you would be wrong. He became, in modern terms, something of a meme. He also gets a mention in 'The Boy's Own Book' by William Clarke, which was was published in 1828. This book mentions 'a blind young man … who may be often seen about the streets of London' and says that he turns the paper into 'the likenesses of a great number of things, animate as well as inanimate' although 'they are, we must confess, but rude resemblances'. (You will note that the drawings and much of the text of this passage are remarkably similar, not to say identical to, those in ‘Sports and Pastimes’ from 1676.)

Amazingly, this book also contains an engraving of the blind busker in action, although, unfortunately, the fan he is demonstrating obscures his face. I imagine that the boy by his side may be there to guide him around and protect his takings from thieves.

Nor was this all. The blind busker became known in France when 'Manuel des Jeunes Gens', a translation of 'The Boy's Own Book', was published in Paris in 1931 (though his picture was not reproduced) …

… and he was also mentioned in a section about ‘Papel Proteo’ (another name for Troublewit) in 'El Brujo en Sociedad' by D J Mieg, which was published in Madrid in 1839. The relevant section reads, roughly, 'more recently the London public will not have forgotten a blind young man who for some years made himself admired in the streets of that metropolis for the singular dexterity with which he knew how to handle said paper.’

The last clear contemporary mention of the blind busker comes from a section about 'Puzzle Wit' in 'The Boy's Holyday Book', which was published in London around 1844. It says ‘Most of our readers, we presume, will have seen a man about the streets producing the likeness of a multitude of articles through the transmogrifications of a piece of folded paper’ but also mentions 'the poor blind fellow whose ingenuity enabled him to get a living by their exhibition'.

Beyond this, unfortunately we know little about the blind busker, neither his name, nor his ultimate fate. Still … he appears to have made a mark in the historical record that would surely have far exceeded his expectations.

PS From prestidigitateur to transmogrifications, a rewarding journey for someone like me who loves unusual words!

Very interesting!

Awesome! Thanks for your research