The Book of Hours of Catherine of Cleves is among the most beautiful of all medieval illuminated manuscripts. It was begun around 1430 and finished around 1440.

Those pages of the manuscript that still survive (a few are missing) are now owned by the Morgan Library and Museum of New York and, helpfully they have made a high res copy available online. (If only more institutions would do this … ) The MS is justly famous not only for the high quality of the main images but also for the fascinating objects that appear in the borders. It is well worth spending a few moments of your time glancing through the pages.

Page 306 of the work is devoted to St Agatha, and you will immediately notice that there are two boxes at the foot of the page, the lower one being decorated with the words ‘St Agatha’ in gold. To either side the boxes are shown opened out, revealing the jewellery that they contain. They are usually interpreted as gift boxes, but that seems odd to me. Gifts, I feel, might have merited much more expensive containers. Storage boxes, perhaps?

The drawings of the open boxes are sufficiently detailed that we can see exactly how they were made, by cutting, slitting and folding a square of … well … either parchment or paper. It isn’t possible to say which, although I lean towards paper simply because the folding is quite complex. I believe that paper folds far more easily, and takes a crease far better, than parchment does.

I cannot begin to find words to express how unique and extraordinary these boxes are. Nothing like them is known from any other source. They are made in a most sophisticated way, in a style that would not otherwise be replicated for hundreds of years. Remember, they date from c1440. We have no other record of a complex folded object from this era.

Of course, traditional scholarship has almost entirely ignored the existence of these boxes (as it has generally ignored paperfolding in all its various guises). The note on the St Agnes page from the Morgan Library for instance simply says ‘Holding her attribute, a pair of pincers with one of her severed breasts, Agatha stands before a textile embroidered repeatedly in gold with a phoenix rising from flames. The motif is appropriate to Agnes as the patron of forging and casting. The cast jewellery in the bottom border provides further reference to this patronage.’ Well, this may be the case … but what about the boxes!

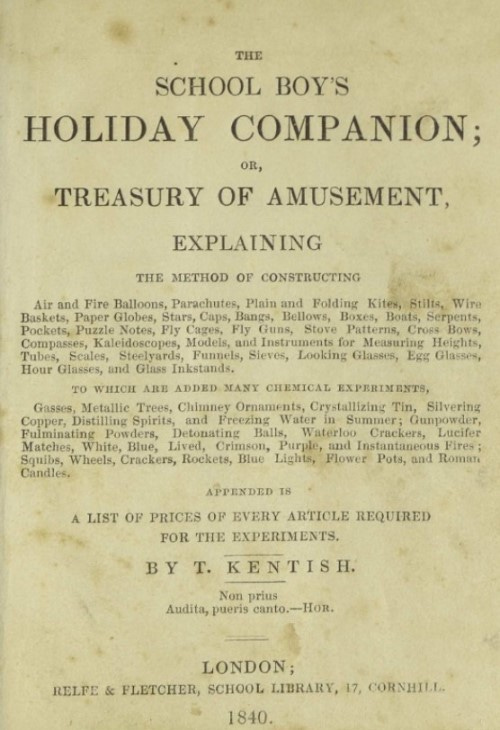

If you have been reading this blog over the last few weeks, you will not be surprised to learn that after 1440 this box disappears from the historical record for, wait for it, 400 years, until, in 1840, it turns up in a book by T Kentish called ‘The School Boy's Holiday Companion’.

It is not obvious how the author came to know of this design. Unlike in the case of, for example, the Paper Boat, there is no chain of written mentions of this box leading back into the past. It disappears after 1440 and reappears in 1840 with no trace in between.

Because the second half of this book is about chemical experiments, T Kentish is probably the Thomas Kentish who wrote a much more famous book ‘The Pyrotechnist's Treasury, or, Complete Art of Making Fireworks’ (otherwise known as ‘How to Lose Fingers and Incinerate People’). He also wrote books intriguingly titled ‘The Gauger's Guide and Measurer's Manual’ and ‘A Treatise on a Box of Instruments and the Slide-Rule’ and, indeed, invented an improved type of slide rule himself. None of which explains how he came to know about a long forgotten medieval box.

However, fortunately for us, somehow he did, and once this box was brought back into the spotlight of history it achieved some degree of popularity, appearing next in 'The Boy's Own Toymaker' by Ebenezer Landells in 1859 and regularly in other similar books thereafter. (If you want to browse through the references you can find them all here.)

PS: I mentioned that these boxes were made ‘in a style that would not be replicated for hundreds of years’ and I better back that statement up. They hold together without glue using a system of interlocking tabs and pockets. It’s a very familiar system to us today, but it is also an essentially modern one. The next earliest design I know of that uses a similar system is this one from the 'Teacher's Manual for Prang's Shorter Course in Form Study and Drawing’ by John S Clark, Mary Dana Hicks and Walter S Perry, which was published in Boston, New York and Chicago in 1888.

PSS: I have added Chat to this substack. You can still leave comments in the normal way, but why not sign up for the Chat facility and contact me like that? I would love to hear from you.